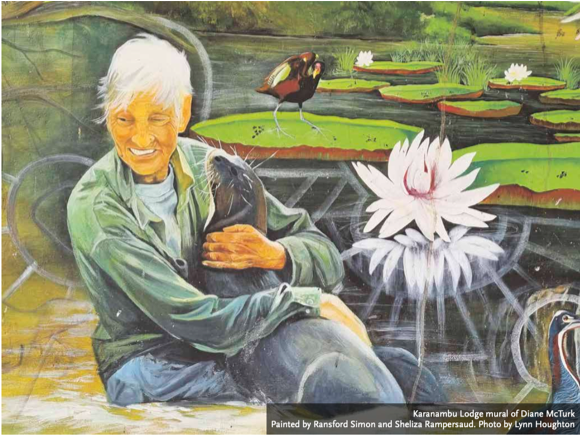

The Otter Lady

Those were, of course, different times, so perhaps the way in which Diane McTurk found her herself at the forefront of ‘ecotourism’ in Guyana might not happen in the same way today. Nonetheless, she was in many respects ahead of her time in realising that wildlife – which would need protecting – would be a key attraction for visitors to the region where she had grown up, writes travel writer Lynn Houghton

A momentary breeze comes off the Rupununi riverand filters through the Karanambu compound, where I am cooling off. Thirty miles of river run through this ranch, and it is alive with birds, giant river otters and dozens of species of fish. A huge mango tree provides relief from the scorching sun, and those who can, retreat to hammocks.

On International Women’s Day, some of us will remember the fierce conservationist Diane McTurk. It is a long overdue tribute, as she dedicated much of her life to saving the unique species she had grown up with in the resource and water rich country of Guyana. And she understood too the importance of bringing tourism to the interior to ensure the future prosperity of the region.

Throughout Guyana, Diane McTurk was known to many as ‘The Otter Lady’, but others will remember the consummate host and early pioneer of tourism. The void – the reservoir of grief for her death in December 2016 at the age of 84 – is still palpable on my first visit here.

Guyana’s shoreline lies along the Atlantic Ocean, and the country is bordered to the west by Venezuela, to the east by Suriname, and it stretches south 2,249km to Brazil. Most of the population lives along the coast, congregating around the capital, Georgetown. It wasn’t until the 1990s that there was a road connecting Georgetown to the inter-ior and it still takes about 13 hours on the Linden–Lethem road to navigate through the country’s dense rainforests, undulating mountains and sprawling grasslands to reach the Brazilian border. The Rupununi’s biggest export was once balata, a rubbery material that was made from the extracted juice from the bully trees.

In 1983 Diane established Karanambu Eco Lodge to share her world with paying guests. On arriving there, I meet Melanie McTurk, Diane’s niece, who not only deals with the day-to-day running of the lodge, but is also car¬rying on her aunt’s conservation work.

“I think it was when Karanambu Lodge was included in the

list of Green Destinations’ Top 100 Good Practice Stories – and that it was competing against entire countries! – that I realised how important our work here is,” she recalls.

She explains: “The 1980s saw the collapse of this area’s economy, mainly due to the winding down of the balata industry and problems with cattle ranching. This eco¬nomic calamity fuelled an uprising. The rebellion was put down by the national government, but subsequently many Indigenous people were punished. Due to the unfairness of the suppression, coupled with the increase in hunt¬ing, gold mining and illegal timber-felling, ranch owners found themselves becoming activists.”

One of Diane’s great passions had been the hand rear¬ing of young, abandoned and orphaned giant river otters (Pteronura brasiliensis). Once rehabilitated, they were reintroduced to the wild. It is reported that one of these orphans even came back to the compound at Karanambu, bringing her family with her. They might not have been the most beautiful creatures, but their intrinsic behaviour, their frolicking and grooming endeared them to Diane.

But why so many orphans? In the 1980s, adult otters could fetch $US200 per pelt and, as there was the belief amongst many that they were reducing fish stocks, they were regarded as pests, and killing was condoned. Diane would ask people to bring her any young otters who would have been left to die after their parents were killed. She then reared them herself, the tiniest creatures kept in her bathroom.

The McTurk roots are firmly in Guyana. Diane’s grand¬father Michael had been Protector of the Amerindians for the entire Essequibo region. His son, Edward ‘Tiny’ McTurk, Diane’s father, was known for his association with David Attenborough and for being featured in the 1950s BBC series Zoo Quest.

Diane was born in 1932 and grew up learning about the extraordinary flora and fauna of this region, which included the giant river otter, giant anteater, giant arma¬dillo, giant freshwater fish, capybara (a very large rodent) and over 400 species of bird.

She left Guyana to attend Wychwood School in Oxford, England, and then moved to London to work as an actress.

Diane wanted visitors to experience the tranquillity and abundant wildlife that are key features of this part of the Rupununi

In 1969 she returned to Guyana to celebrate the country’s independence and subsequently became press officer for The Guyana Sugar Producers’ Association. She moved back to England briefly and worked in corporate public relations, but returned to her Rupununi roots in 1976.

Like all the cattle ranches in the area at the time, Karanambu had suffered a series of misfortunes with disease epidemics decimating herds, and with difficul¬ties protecting the cattle from rustlers. As a result, Diane looked for alternatives to make a living. Karanambu was well known for its wildlife and spectacular fishing and had always been a welcome rest stop for unexpected visitors. It was Diane’s idea to launch Karanambu as an ecotourism resort. Her vision was for visitors to experi-ence the tranquillity and abundant wildlife that are key features of this part of the Rupununi. The ecosystem of the Rupununi savannah needed to be preserved in the face of increasing development, so the McTurk family founded the Karanambu Trust, which is dedicated to preserving the ecosystem and wildlife of this region as well as supporting

the traditional lifestyle of the Indigenous Amerindians through the promotion and sponsorship of scientific research and sustainable economic development.

And there is a new problem emerging, as large quan¬tities of fish are being illegally netted. With Karanambu being some 300 miles from the capital, Georgetown, and with only one fisheries officer to monitor the problem, very little is being done to address this. However, a more positive development has been the opening of a wildlife monitoring site and checkpoint, which will be run by a local group, the South Rupununi District Council.

I am sure that Diane would be proud.

Lynn Houghton is a travel and conservation writer. Originally from Alberta, Canada, she now splits her time between London and Hampshire, UK, covering stories on Nature, wilderness travel and rewilding in the UK and Americas. To join this trip to Guyana’s Karanambu Ranch, Lynn was a guest of the Guyana Tourism Authority and her visit was organised by www.wilderness-explorers.com